What’s the Slimy Stuff in Your Poop, and What Does it Mean?

If you’ve ever taken a look at your stool (and if you don’t, do it, it’s a great way to track your gut health) and seen that it has a slimy-looking gel coating, you were looking at an important, and often underappreciated, part of your gut’s defensive layer – intestinal mucus. A little clear mucus is normal, but read on to find out what warning signs to look out for in your poop.

What is mucus and what does it do?

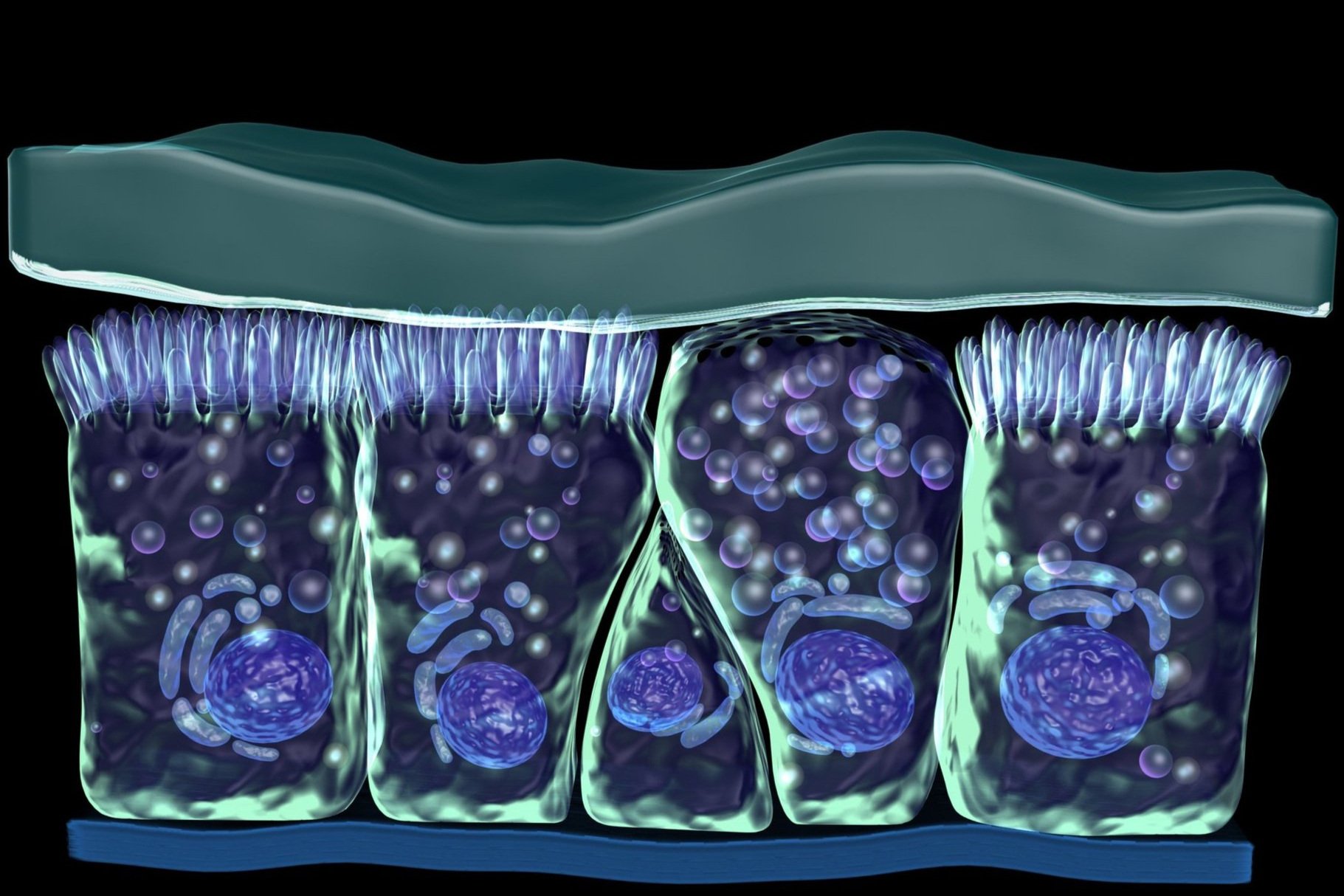

Mucus is a gel-like substance that coats and protects mucous membranes – the tissues that line the body cavities that are open to the outside like the sinuses, lungs and gastrointestinal tract. It’s more than 98% water, held together by mucins, a net of branching proteins frosted with fuzzy plumes of linked sugars at the tips. Humans don’t have the enzymes to break apart the particular configurations of sugars on mucins, so they can’t be self-digested in the harsh environment of the intestines (Pelaseyed et al., 2014).

Salivary glands produce mucus to lubricate food to make it easier to swallow, the esophagus is lined with mucus to help food slide through and, importantly, the stomach is lined with mucus to protect the gastric lining from the intense acidic environment inside. Intestinal mucus plays a vital role in keeping bacteria and harmful substances from interacting with the delicate intestinal cell wall (Marieb & Hoehn, 2010).

What is the Intestinal Mucus Layer?

In the small intestine, a single layer of mucus is secreted from a certain type of intestinal cell called a goblet cell. The flow of mucus away from the cells, along with antimicrobial chemicals secreted from nearby Paneth cells, keep microbes from reaching the intestinal lining and causing inflammation and cell damage. In the large intestine, there are two layers of mucus. A thick layer of gel-forming mucins is anchored to the intestinal cells by what are called transmembrane mucins, and a free-flowing, more viscous layer sits above it. The outer layer helps ease the passing of feces and houses the majority of gut microbes. Here they eat up indigestible fiber and produce beneficial nutrients like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and vitamin K. The inner layer is protective – too thick for bacteria or harmful substances to pass through and damage the cells (France & Turner, 2017).

What happens when the mucus layer stops working

Human enzymes can’t break down mucins, but certain gut microbes can. In a healthy state, the microbes do us a favor, breaking some of the links between mucins so that the mucus can expand, hold more water, and become more viscous. Bacterial metabolites like SCFAs and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) trigger goblet cells to produce more mucin, replenishing the mucus layer. But studies show that a diet low in fiber, the preferred food of most large-intestinal bacteria, forces them to rely on mucins as a food source, degrading the mucus layer more quickly than it can be replenished. The mucus becomes thin, allowing easier passage of microbes, LPS, acids, digestive enzymes and undigested food components through to intestinal cells. Acids, digestive enzymes and pathogenic microbes can directly damage cells, and LPS and food components like gluten peptides can trigger tight junctions between cells to open, allowing the invaders to get into the tissues beneath the cells. This sets off a red alert in the immune system, and the area is quickly flooded with inflammatory cells releasing chemicals that trigger further tight junction opening, damage goblet cells and reduce quality of mucus production, further reducing mucus layer protection. The modern diet is much lower in fiber than humans have historically eaten, with an average far below the recommended 28-35 grams per day. Perhaps as a result, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) rates are on the rise, with patients with IBD like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis showing a reduction in mucus thickness (Desai et al., 2016; Okumura & Takeda, 2018).

In the small intestine, too much gluten or sugar attracting bacteria that form harmful metabolites can break through the mucus layer, causing tight junctions to open and starting the inflammatory cycle that inhibits mucus production.

Stress can also impact mucus production. The gut, or enteric, nervous system actually has more nerves than the central nervous system, and a stressful event can cause release of acetylcholine, triggering goblet cells to dump all their mucin into the intestinal tract at once. This may be why some people suffer from diarrhea when in stressful situations. It takes 4-5 hours for goblet cells to be renewed and mucus production to be restored, but the inner mucus layer is normally replaced every 1-2 hours, so the mucus layer is degraded with stress (Pelaseyed et al., 2014).

How do you know if your mucus layer is impaired?

As your mucus layer is replaced frequently, some gel visible in your stool is normal. However, excessive mucus in stools, colored mucus or excreting only mucus when you have a bowel movement are signs of gut dysfunction. If your mucus is white or other colors, that could indicate inflammation or infection, as immune cells or excess bacteria will color the normally-clear gel. Blood in the mucus could be from something as simple as passing stool that’s too hard, or something more serious, so see a doctor if it persists.

How to improve your mucus layer

Feed your gut microbes lots of fiber to keep them from excessively degrading your mucin. High-fiber foods include minimally processed fruits and vegetables, grains and legumes. Start with at least five servings of vegetables and two servings of fruits per day and work up to eight or more servings of vegetables per day. Drink at least eight cups of liquids per day to keep your mucus hydrated, and avoid excessive amounts of gluten and sugar that can overwhelm your mucus layer’s ability to dilute it and attract too much bacteria to the small intestine.

References

Desai, M. S., Seekatz, A. M., Koropatkin, N. M., Kamada, N., Hickey, C. A.,

Wolter, M., Pudlo, N. A., Kitamoto, S., Terrapon, N., Muller, A., Young, V. B., Henrissat, B., Wilmes, P., Stappenbeck, T. S., Núñez, G., & Martens, E. C. (2016). A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell, 167(5), 1339–1353.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043

France, M. M., & Turner, J. R. (2017). The mucosal barrier at a glance. Journal

of Cell Science, 130(2), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.193482

Herath, M., Hosie, S., Bornstein, J. C., Franks, A. E., & Hill-Yardin, E. L. (2020).

The role of the gastrointestinal mucus system in intestinal homeostasis: Implications for neurological disorders. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10(248). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00248

Marieb, E. N., & Hoehn, K. (2010). Human anatomy & physiology (8th ed.).

Benjamin Cummings.

Okumura, R., & Takeda, K. (2018). Maintenance of intestinal homeostasis by

mucosal barriers. Inflammation and Regeneration, 38(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-018-0063-z

Pelaseyed, T., Bergström, J. H., Gustafsson, J. K., Ermund, A., Birchenough, G.

M., Schütte, A., van der Post, S., Svensson, F., Rodríguez-Piñeiro, A. M., Nyström, E. E., Wising, C., Johansson, M. E., & Hansson, G. C. (2014). The mucus and mucins of the goblet cells and enterocytes provide the first defense line of the gastrointestinal tract and interact with the immune system. Immunological Reviews, 260(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12182

Williams, J. M., Duckworth, C. A., Burkitt, M. D., Watson, A. J., Campbell, B. J.,

& Pritchard, D. M. (2015). Epithelial cell shedding and barrier function: A matter of life and death at the small intestinal villus tip. Veterinary Pathology, 52(3), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985814559404